Should You Give Your Baby a Pacifier? What the Research Actually Says

Oct 22, 2025

If you’ve ever felt torn about offering your baby a pacifier you’re not alone.

Some say it’s a lifesaver, others call it a dental disaster waiting to happen.

So what’s the truth?

Is it okay to give your baby a pacifier, and if yes which kind?

Let’s unpack the latest research (and what I’ve seen in my own practice) to finally put this debate to rest.

Babies Suck for Comfort and That’s a Good Thing

Sucking isn’t just for feeding. It’s an instinct your baby is born with one that helps them feel calm, safe, and settled.

That’s why many babies start sucking on their fingers or thumbs as early as in the womb! It’s their way of self-soothing.

But here’s the challenge: once a baby starts relying on their thumb for comfort, breaking that habit later can be really tough. You can take away a pacifier but you can’t take away their thumb.

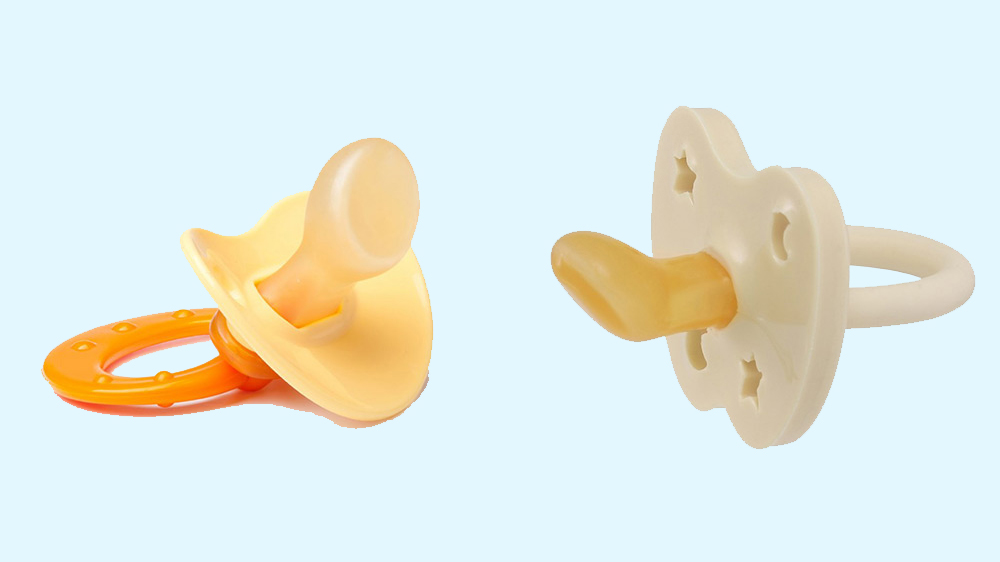

This is where orthodontic pacifiers come in as a healthier, more controllable option.

The Study That Changed Everything

A recent observational study conducted on about 200 preschoolers (aged 3–5 years) explored the long-term oral effects of using orthodontic pacifiers during infancy.

These were children who had used orthodontic pacifiers as babies and the findings were fascinating.

Here’s what the researchers found:

🔹 Lower risk of thumb and finger sucking habits:

Children who had used orthodontic pacifiers were far less likely to develop thumb or finger-sucking behaviours later.

This suggests that the pacifier had already fulfilled their early sucking need, meaning they didn’t need to find an alternative (like their thumb) for comfort.

🔹 Better oral and dental development:

Unlike traditional pacifiers, orthodontic pacifiers are designed with a flatter nipple and angled shape that allows for proper tongue placement and jaw growth.

This means they don’t put the same kind of pressure on developing teeth and palate preventing issues like open bite or crossbite that older-style pacifiers used to cause.

🔹 Easier and less stressful weaning:

Only 2.5% of parents reported that their child was stressed when it was time to wean off the pacifier.

That’s an incredibly low number proving that if introduced early and used thoughtfully, weaning doesn’t have to be a nightmare!

Why the “Orthodontic” Design Matters

Let’s break this down simply.

A regular pacifier has a rounded nipple that can push against the upper palate when sucked for long periods, which over time may influence teeth alignment.

An orthodontic pacifier, however, is shaped to mimic the natural position of a mother’s nipple during breastfeeding flatter on the bottom, curved on top encouraging the tongue to rest forward and the jaw to close correctly.

This design helps support:

✔ Proper oral muscle development

✔ Healthier jaw alignment

✔ Natural swallowing and tongue motion

So, if you’re planning to offer a pacifier, an orthodontic one is always the smarter choice.

When and How to Wean the Pacifier

While pacifiers can be wonderful tools in the early months, knowing when to let go is just as important.

I recommend weaning by 6 months or at the very latest, by 1 year.

At this stage, your baby’s need for sucking as comfort naturally starts to decrease, and it’s much easier to transition away from the pacifier before it becomes an emotional crutch.

Here’s how you can make the process smoother:

- Begin by limiting pacifier use to naps and nighttime only.

- Offer alternative soothing cues like a comfort love, soft humming, or gentle back rubs.

- Maintain a predictable bedtime routine so your baby feels secure even without the pacifier.

Once you remove the pacifier, it’s common for babies to take longer to fall asleep or wake up more frequently for a few days. That’s normal.

To maintain good sleep without the pacifier, I recommend sleep training, a structured, responsive way to help your baby learn self-soothing skills and sleep independently.

What This Means for You and Your Baby

If you introduce an orthodontic pacifier within the first 3 months, it can actually help your baby’s natural development and save you the thumb-sucking struggle later on.

Here’s why:

- It satisfies your baby’s innate need to suck for comfort.

- It’s easier to control (you can remove or replace it when needed).

- It doesn’t interfere with breastfeeding when used correctly and early.

- It promotes a safe, self-soothing mechanism which is also an early foundation for independent sleep.

And when it’s time to stop, you can do it gradually and lovingly without tears or stress.

From a Sleep Consultant’s Lens

I often see babies who struggle to sleep independently because they rely heavily on feeding or rocking to soothe themselves.

Introducing a pacifier (especially an orthodontic one) can be a gentle bridge toward self-soothing, helping your baby link comfort with something other than you.

Of course, it’s not the only tool. A consistent bedtime routine, sleep-conducive environment, and age-appropriate nap schedules matter just as much.

But pacifiers when used thoughtfully can absolutely be a part of your baby’s healthy sleep toolkit.

If you’d like to dive deeper into building healthy sleep and soothing habits, here are some next reads you’ll love:

- What Is Sleep Training? The Real Truth Behind Helping Your Baby Sleep

- 6 Medical Red Flags to Address Before Sleep Training Your Baby

Final Thoughts

Parenting is full of “shoulds” and “should-nots,” especially when it comes to baby sleep and comfort. But science is clear when used properly, orthodontic pacifiers can support healthy development, reduce thumb-sucking, and make soothing easier for your baby (and you!).

If you’re ready to go beyond pacifiers and build strong, independent sleep habits check out my Infant Sleep Training Program.

It’s a gentle, evidence-based program designed to help your baby sleep better without sacrificing connection or comfort.

Look at our reviews

References

Lione, R., Franchi, L., Fanucci, E., & Cozza, P. (2019). Poor oral habits and malocclusions after usage of orthodontic pacifiers: An observational study on 3–5 years old children. BMC Pediatrics, 19(1), 295. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-019-1668-3